Read the original article on DavidsonLocal.com.

The Davidson County Opioid Settlement Fund Committee is looking at hiring a coordinator to oversee how to use the $12 million the county will have in opioid settlement funds.

Currently Davidson County has been paid $6.9 million in opioid settlement funds and is slated to receive another $1.9 million in the 2025-2026 fiscal year, according to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.

These settlement funds are part of the $56 billion North Carolina received from the national opioid settlement lawsuit in 2021. Davidson County is slated to receive $23.4 million over the next 13 years.

On Monday, North Carolina Attorney General Jeff Jackson announced North Carolina will receive $145 million in a settlement with Purdue Pharma and its owners, the Sacker family. Davidson County is slated to receive an additional $2.3 million in funding from this recent settlement. Most of these funds will be distributed in the next three years according to the NC Department of Justice.

This would bring the Davidson County Opioid Settlement fund to approximately $12 million, which has mostly not been used. Last year, the county approved $1.2 million from opioid settlement funds toward the Medically Assisted Treatment program at the Davidson County Jail.

During the meeting on Tuesday, several committee members vented frustration on the lack of progress, stating they have met for several years and have yet to come up with a clear plan on how to spend these funds.

Lillian Koontz, director of the Davidson County Health Department, said she proposed the idea of hiring a coordinator for the opioid settlement funds over a year ago.

“These were the exact things we talked about and here we are a year later,” said Koontz. “We have not spent any money; we have not done any coordination… I strongly support using some of the opioid funds to identify a human being to do the research for us, to say how much money we have, to vet the programs and then bring solid ideas to us. As it is now, we just come into a meeting, hear some ideas and then we don’t meet again for several months and we are not doing anything.”

The committee members voted to send their recommendations to hire a coordinator/director to oversee the county opioid settlement funds to the county commissioners for approval during their meeting on June 23. If approved, the county manager would work with the county human resource director to create a job description and begin the hiring process.

Committee member Billy West, executive director of Daymark Recovery Services, said the committee should also consider granting smaller requests, under $10,000, to community partners until the new coordinator can be hired.

“It could be three or four months before that person actually gets (here),” said West. “In the meantime, there are other things that can be done so we are not viewed as a bunch of people sitting around with $12 million and won’t even spend $20,000 of it on local things.”

Mike Loomis, founder of Race Against Drugs, currently has a request for approximately $6,000 in funding from the Davidson County Opioid Settlement Committee and has not had any response from the group, or had his request sent to the county commissioners.

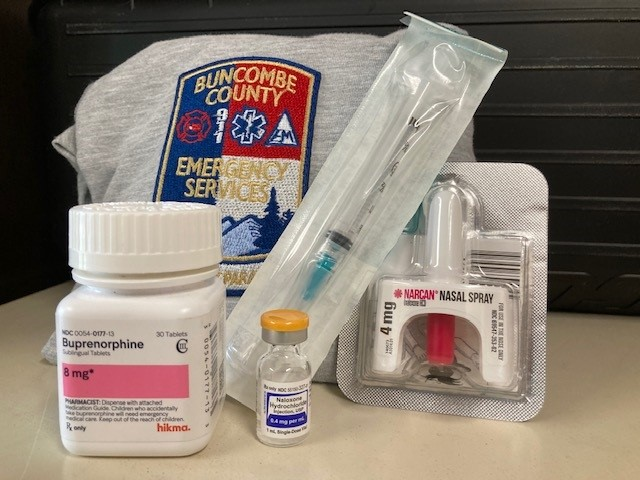

He is currently paying for educational materials, like several billboards to raise awareness of the impact of fentanyl overdoses, out of his own pocket. He purchases doses of Naloxone and distributes them in the community. Race Against Drugs also has an awareness event at Breeden Insurance Amphitheater in Lexington on Aug. 9.

Loomis said he is disappointed in the progress of the opioid committee, especially when it comes to supporting those in the community who are “boots on the ground” in battling opioid addiction.

“They are just waiting for another life to be lost,” said Loomis. “I have been doing this by myself for so long and I am up against the stigma of people struggling with addiction. I am disappointed, but I will keep doing what I do.”

County commissioner Steve Shell said the opioid committee can already bring any spending request for use of settlement funds for approval by the county commissioners.

The committee also discussed other options available to combat opioid addiction, including Naloxone (Narcan) vending machines, which would be available to citizens after hours. Several members showed hesitation on placing these machines in the community but voted to create a list of community partners which are already providing Naloxone.

The providers list would be available on the United Way 211 system. NC 211 is an information and referral service that connects people with local resources 24-hours a day.

Major Billy Louya, who oversees operations at the Davidson County Detention Center, gave an update on MAT program. He said since Jan. 1, there have been 27 participants in the program, which equals about 1% of inmates booked into the jail.

The MAT program uses once a month medication administered at the jail, instead of transporting inmates to local treatment clinics weekly and includes a peer support program after the inmate is released from detention.

The committee also discussed finding additional community partners to provide more post incarceration peer support.

The Davidson County Opioid Settlement Fund Committee meets quarterly and includes representatives from organizations impacted by opioid addiction, including the health department, law enforcement, family services, emergency services, county government, elected officials and community partners involved in prevention and recovery.