Read the original article on the North Carolina Health News website.

By Rachel Crumpler

A life lost in Buncombe County in 2022 still weighs on — and motivates — Shuchin Shukla, a family physician who specializes in addiction medicine.

A community paramedic had responded to an overdose involving a person recently released from jail. After reviving them, the paramedic told the patient about a soon-to-launch program that would start people on a medication used to treat opioid addiction after an overdose.

“That would be amazing if you had it now, I would like to start now,” the patient said, according to a shift note of the encounter.

But the program was still 10 days from launch.

Soon after, the person used again, experienced a second overdose and went into cardiac arrest. They later died at the hospital.

“For the team working on this, the case hit home that every moment of every day matters for patients. At any minute, they’re at risk of dying or having an overdose,” Shukla said. “That’s how critical this is.”

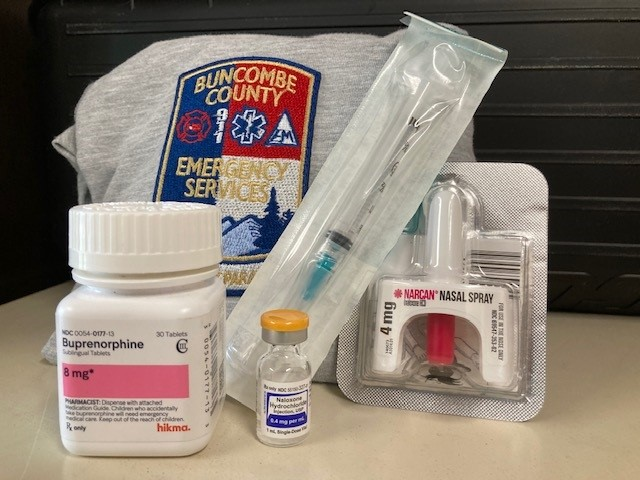

For months, Shukla had been working with Buncombe County Emergency Medical Services to launch Buncombe Bridge to Care, a project to equip paramedics to administer buprenorphine — a medication proven to ease opioid withdrawal symptoms, reduce cravings and support long-term recovery for people with opioid use disorder — when responding to overdoses or others in the community struggling with addiction.

Since March 2022, Buncombe County EMS community paramedics have been able to administer buprenorphine treatment on the spot in what Shukla said can be a “lifesaving foot in the door.”

Buprenorphine is one of three medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat opioid use disorder. It’s considered best practice for treatment when paired with counseling. As a longtime prescriber of these medications, Shukla knew their effectiveness firsthand. Yet only an estimated one in five people who need them receive them, according to government statistics. They are hindered by barriers like a lack of access to medical providers and transportation and by fleeting motivation to seek treatment.

Many people who survive an overdose decline to be taken to the hospital, which leaves EMS personnel as their only point of contact with the health care system. Those interactions can be a critical window: Research shows people who survive an overdose are at heightened risk of subsequent overdoses.

Overdose deaths like the one above have led Shukla and others to see EMS as a crucial link that can bring addiction treatment directly — and immediately — to people in crisis. A dose of buprenorphine can reduce the risk of another overdose for up to 24 hours.

Buncombe is among 30 EMS agencies in North Carolina approved by the state Office of Emergency Medical Services to administer buprenorphine for up to seven days to manage withdrawal and support early recovery as a bridge to a long-term treatment provider, according to a spokesperson at the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

“I see it gaining even more traction moving forward,” said Mike Campbell, training division chief at Stanly County Emergency Medical Services, one of the first agencies in the state to begin field-based buprenorphine in 2019. “I think, before too long, it will become the norm.”

An emerging practice

EMS-provided buprenorphine is an emerging practice in North Carolina — and across the country — aimed at reducing opioid overdose deaths and increasing treatment engagement.

Traditionally, paramedics’ work ended once they administered naloxone, reversed the overdose and offered transport to the hospital. But as overdose calls surged, EMS crews often responded to the same people again and again. Naloxone, the fast-acting opioid overdose reversal medication (brand name Narcan), can cause unpleasant withdrawal symptoms, and that pushes many people to use again soon after being revived.

It was discouraging.

“A lot of medics would reverse people over and over again until they finally saw them die, and that just really burned out a lot of our medics,” James “Tripp” Winslow, medical director of the state Office of Emergency Medical Services, said at the Opioid Overdose Response Teams: Best Practices Summit in Asheville earlier this month.

That pattern prompted some EMS leaders to consider how to better serve overdosing patients. Their answer: expand the toolkit. They saw an opportunity to go beyond reviving people to helping start them on a path to recovery by administering buprenorphine in the field.

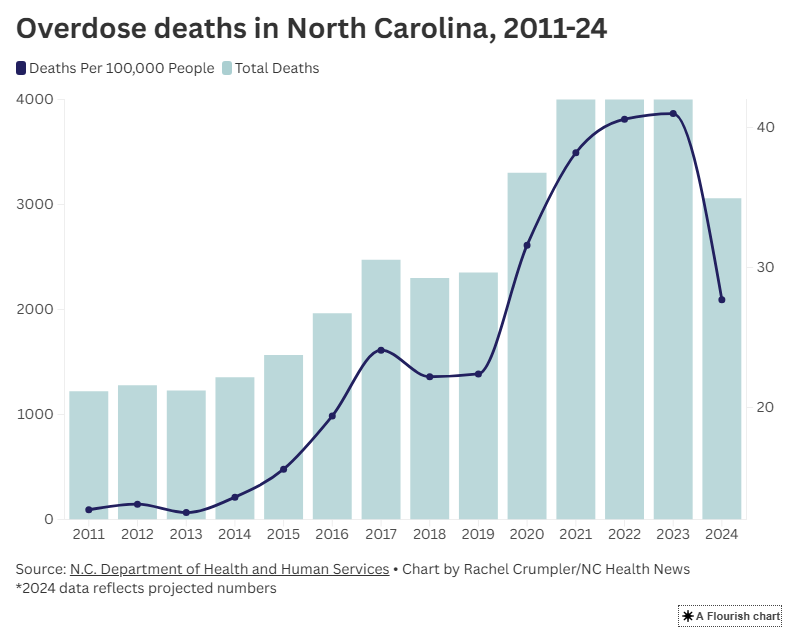

In 2024, EMS agencies across North Carolina responded to 25,389 suspected overdoses, according to data provided to NC Health News by the state Department of Health and Human Services. As of Oct. 17, North Carolina EMS agencies have responded to 17,901 such calls in 2025 so far.

“I think we’re the right people to initiate [buprenorphine] at the right time,” said Campbell from Stanly County. “If not, they may never make it to the clinic, whether they decide and change their mind and don’t want to go into treatment or ultimately, unfortunately, pass away from a fatal overdose.”

“I view medication-assisted therapy as a lifesaving intervention,” he continued. “Without it, we’ve seen what the other end is: We lose lives.”

It’s a capability that complements a growing number of post-overdose response teams — many based within EMS agencies — that are connecting people who struggle with addiction to ongoing recovery support, harm reduction resources and treatment.

Shukla said it doesn’t take long for paramedics to get comfortable screening patients and administering a dose of buprenorphine when it’s appropriate.

“Paramedics are realizing this is not a dangerous med,” Shukla said. “It works so well, and I think more cities and counties will embrace it.”

Bringing addiction treatment to the front lines

For Stanly County EMS, buprenorphine in the field has become a key tool in responding to opioid-related calls, said Campbell, the agency’s training division chief.

Not everyone accepts the medication immediately after an overdose, he said, but for those who do, it can quickly ease withdrawal symptoms and stabilize them long enough to connect with care.

Others may decide to start later, often after talking with peer support specialists who have their own recovery experiences.

When they do, paramedics are ready.

“We are available to patients at 2 o’clock in the morning if that’s when they decide that they want to enter recovery,” Campbell said, noting that community paramedics in the county are available 24 hours a day. “That window is very, very small.”

He knows from personal experience.

“I’ve seen it with my own sister — she’s ready to go to detox, and by time she gets to detox, she’s changed her mind,” he said. “One of the most important parts is being able to respond immediately at the time of need or the time of crisis to get them connected at that very moment.”

Shukla, who has led multiple training sessions this year on post-overdose response teams and EMS-provided buprenorphine across the state, said that field-based buprenorphine helps break down key barriers to treatment — limited clinic hours, lack of transportation and insurance — making it easier for people to take that first step of starting medications for opioid use disorder.

“Overdose survivors are at the highest risk of dying today, tomorrow and the next day,” Shukla said. “The question is: How can we get to those folks the fastest? How can we get to them the most effective way?”

Making medications for opioid use disorder more accessible is a statewide goal, and paramedics are increasingly a vital point of access.

A bridge to longer-term treatment

The up to seven days of buprenorphine that paramedics can typically provide, circling back to the person daily to administer doses, are not replacing clinics. They’re bridging the gap until that person is connected to a longer-term treatment provider. Referrals come from probation officers, hospitals and family members who have a loved one struggling with addiction, not just overdoses.

That bridge is especially useful in rural areas with few prescribers

Edgecombe County, which has nearly 50,000 people, has only one doctor’s office that prescribes medications for opioid use disorder, said community paramedic Dalton Barrett, who also leads that county’s post-overdose response team. Providing buprenorphine has been a game-changer since they started the practice there in 2023.

“We knew that there were a lot of people out in the community that had no idea about medication-assisted treatment,” Barrett said. “The idea was to get someone ‘boots on the ground,’ to go out to the community to educate people … before an overdose, after an overdose, during an overdose event … to tell them kind of what the options were and be able to provide it.”

Barrett said he’s dosed patients in a range of settings — including the parking lot outside a person’s job — taking treatment directly to someone who had overdosed multiple times.

“It’s important that the patient doesn’t go into withdrawal before they get to their appointment, because if they do, then their likelihood of going to that appointment is probably going to be pretty low,” Barrett said. “We want to make sure that they’re as stable as possible before they get in front of that provider.”

So far this year, Barrett and another community paramedic have initiated 76 patients on buprenorphine — up from 22 patients served in 2023 and 67 patients in 2024.

Barrett and other paramedics at EMS agencies across the state can also offer alternate destination transport, where they can take someone to their first appointment with an addiction treatment provider.

For EMS-provided buprenorphine to succeed, communities must have those treatment providers in place for follow-up care — which is a challenge in some areas.

“There’s lots of counties where there’s really no options for outpatient-based opioid treatment,” said Winslow, the medical director of the state Office of Emergency Medical Services, at a recent conference describing the state of EMS medication-assisted treatment bridge programs. “If they can’t get an option for outpatient-based opioid treatment, EMS and the community paramedics really can’t carry that program on. They can’t keep following those up.”

From new practice to standard of care

EMS teams providing buprenorphine is still a relatively new practice, so the research is still developing.

But early findings in North Carolina and elsewhere show some promise.

In New Jersey, the first state to authorize paramedics to administer buprenorphine at the scene of an overdose in 2019, patients who received buprenorphine after naloxone were nearly six times more likely to have engaged with treatment within 30 days, according to a 2023 study published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine. However, the study did not find that people who took buprenorphine from EMS were less likely to overdose again compared with patients who didn’t receive the addiction medication.

In Wake County, a 2025 study published in Prehospital Emergency Care reviewing the first year of paramedics administering buprenorphine found that 92 percent of screened patients who met the eligibility criteria for buprenorphine accepted it. Nearly half of patients who received buprenorphine followed up with the nonprofit outpatient treatment provider SouthLight. One in 10 patients who received buprenorphine from EMS remained in treatment at the end of the yearlong review period in July 2024.

Similarly, Buncombe’s first year results, published in a 2024 study in the Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, showed that paramedics started 118 patients on buprenorphine, and 104 of them followed up at a clinic for continued care. More than two-thirds remained engaged in treatment after 30 days.

Now, Buncombe paramedics are even busier, starting about 30 to 40 patients on buprenorphine just in the past month, said Brandi Hayes, Buncombe’s post-overdose response team peer support specialist coordinator, at an overdose summit earlier this month.

“More people are getting access to care,” said Hayes, who helps patients transition from receiving buprenorphine from paramedics to seeing outpatient treatment providers.

While data on the effectiveness of EMS-initiated buprenorphine is still emerging, the evidence behind buprenorphine itself is already clear.

“The science is so powerful at how lifesaving it is, particularly for high-risk groups like people leaving jails and prisons or people surviving a nonfatal overdose,” Shukla said.

His hope is that EMS offering buprenorphine after an overdose — or to those with ongoing opioid use issues — will become as routine as giving aspirin for chest pain.

“Buprenorphine saves much more lives than aspirin ever will,” Shukla said. “It’s so much more effective, and yet it’s so far away from being seen as that essential of a response to the situation of overdose or ongoing opioid use. That’s where we need to be as a society.”